Although the concept of species is a bit more fluid than we once thought, as we understand more and more how one species evolves into another, there is a set standard for a species. It is defined as any individual that can interbreed with another, and produce viable offspring on to the 3rd generation. A intriguing recent study on dogs provides some incidental support for the idea that we can at times magnify the differences between fossil species because we lack their DNA. If there is more cranial difference between dog races than there is between all species of Carnivora (including seals and tigers!), then there can be times when, by only looking at fossils, we may conclude that there are different species rather than one species with a large skeletal diversity. This becomes more likely when we consider that most of evolutionary history is famously described as fossil teeth breeding with other fossil teeth to produce new fossil teeth.

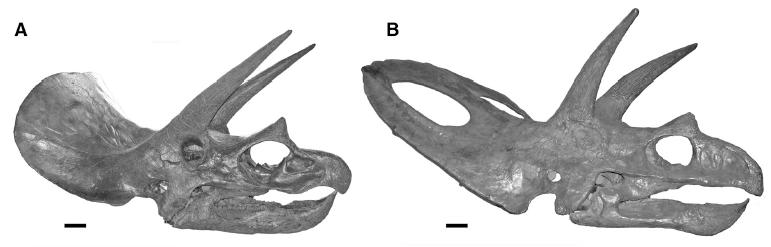

So it is reasonable to discover that Triceratops sp. and Torosaurus sp. are one and the same- it is a reasonable confluence of the data that we had previously. However, since Triceratops sp. was discovered first, by long-standing biological tradition, Triceratops will remain the same, and Torosaurus shall disappear, just as Brontosaurus sp. gave way to Apatosaurus sp.

However, all of this is a great deal different than the case of Pluto and the planets. While the species definition is based in some measurable reality (albeit with minor disagreements on the meanings of the measurements), the planet definition is purely arbitrary. For years we were excited to consider that there were probably more planets than the nine that we have/had. (Consider Xena/Gabrielle that became Eris and its moon Dysnomia, larger than Pluto and Charon.) When more and more planets began to be discovered, including larger ones than Pluto, as you discussed in the podcast, it became clear that we needed a definition of “planet” better than what we currently had. But this definition needed to also encompass all of the extra-solar planets that we have discovered over the last couple decades.

Definitions were bantered around, but it was finally decided at that pivotal meeting a few years back, in which Pluto was demoted. Unfortunately, there was more politics than science at this meeting. Most of the astronomers who have the right to vote on this issue were not present at the conference, and most of those who were present at the conference were not present at the meeting when this was voted. There was a scientific outcry afterward of foul play, that often gets ignored in media reports. There are significant problems with the current definition of a planet, most notably that extra-solar planets do not necessarily meet the definition, and that, when strictly followed, Earth itself and most of the planets in our solar system have also not “cleared their orbits” and therefore aren’t planets.

Subsequently there were changes to the definitions, creating “Plutoid” as well as “Dwarf Planet”, to cover a few select objects.

What also gets ignored in many subsequent media reports is that Pluto remains a planet. Pluto is a “Dwarf Planet”, which cleverly can be defined as either not a planet, or a type of planet, depending on one’s proclivities.

In the end, the term “planet” is entirely defined by us humans, without regard to anything specific in nature. In other words, we choose how to define a planet, and whether or not Pluto is one. A species, however, is something that is inherent in nature. We may have enjoyable arguments on just how one defines it, but it is a concrete entity, and its existence is integral to the science of biology. When it was discovered that Triceratops and Torosaurus were one and the same (which, it seems to me, seems to be likely at this point but not conclusively “proven”), we were then obligated to go with the earlier name, Triceratops, and Torosaurus ceased to exist.

Personally, I think this helps us understand where Tundro of the Herculoids came from…